Movie About Boy India Likes to Draw

S aroo Brierley is fresh off the plane, sitting in a movie studio office overlooking Beverly Hills, once again adapting to an alien environment. The Academy Awards are on Sunday, and Los Angeles is in full Oscars mode, with limousines ferrying stars, executives and other film folk through the winter sunshine to receptions and cocktail parties.

The mood is febrile. Some nominees starve themselves in order to fit into tuxes and gowns. Others get last-minute Botox injections. Soothsayers stake reputations on whether Moonlight will spoil La La Land's expected sweep, or whether Denzel Washington will pip Casey Affleck. The Hollywood Reporter has published an article headlined: "Nervous about the Oscars? 4 tips for dealing with panic attacks." And of course there is Hollywood's expected declaration of war against Donald Trump in the podium speeches.

Brierley, casual in a white T-shirt and black jeans, shrugs off the frenzy. "You can really submerge yourself in it and get lost – let it cloud you. But I just don't really want to get into it. I'm sitting back, listening, you know, taking it in day by day."

That is quite a feat, given his stake in this year's awards. The story of his life, Lion, is up for six Oscars, including best picture. "The feelgood movie we all need," blares the promotional blurb, and for once the hype may be justified.

It tells the story of how, in 1986, Saroo, an illiterate, impoverished five-year-old in rural central India, got separated from his brother at a railway station in Burhanpur, and accidentally ended up alone on a train that took him almost a thousand miles to Kolkata (then called Calcutta). Unable to speak Bengali, and unaware of the name of his home town, he had no way to return. He lived as a street urchin and survived on his wits and scraps of food. He was later taken in by an orphanage, and was eventually adopted by an Australian couple, Sue and John Brierley, who took him to start a new life in Tasmania.

A quarter-century later came the implausible twist. Saroo – by now a robust, happy, windsurfing, fully fledged Aussie – used Google Earth, a handful of visual memories and immense dedication to identify his home town: Khandwa, in central India. In February 2012 he travelled there and – spoiler alert – found his biological mother, Fatima.

"It was such a pivotal moment," he recalls, seated in a low chair high above the LA traffic. "She saw my face, after 25 years of separation. I still have that sort of babyface within me. A mother like her would not have forgotten one of her children's looks. She knew who I was, and I knew who she was. The memory of her face had been embedded in my mind for such a long time."

Fatima did not speak English and he had forgotten his Hindi. It did not matter. "We were tactile, using our hands and faces to express what we felt. The tears spoke for themselves."

Lion's box office numbers speak, too: it is now roaring past a $100m take. Directed by Garth Davis, it stars Sunny Pawar and Dev Patel as young and older Saroo respectively, and Nicole Kidman and David Wenham as his adoptive parents. It has been largely well reviewed, and has earned cast and crew multiple nominations and awards, but it chugs into the Oscars as a longshot contender.

Will it be nerve-racking to sit in the Dolby Theatre? Brierley, affable and easygoing, bursts out laughing. "No! It definitely won't be nerve-racking. The only nerve-racking thing is these cameras. I know it scares my dad. Because they're all going flash-flash-flash, and people are saying: 'Over here, over here, this way, this way.'"

Saroo can vividly recall his early childhood – the hunger and scavenging, the bond with his mother and siblings – but can also "disassociate" himself from the experience, he says. "I've moved on. I've moved to Australia, to amazing parents who gave me unconditional love, to being educated and submerged in an amazing country and society."

The Weinstein Company, a shrewd awards strategist, has marketed the film as a feelgood antidote to dark, turbulent times – the true story of a life lost and found across continents and cultures. It helps that Brierley is an upbeat, engaging soul who is thankful for his good fortune. "At the end of the day, this is a story about a boy going through trials and tribulations and triumphing at the end," he says.

On a night when much will be viewed through the prism of the Trump presidency, the story of a dark-skinned foreigner finding welcome in the west could be viewed as political, but Brierley hopes it won't.

"I really don't want to talk about politics – at all," he says, the only time in the interview when he prickles. "I tend to keep politics out of this story, and I think that goes for everyone else that is producing the movie."

He pauses, weighing his words. "I just hope it touches those politicians and bureaucrats to open their hearts up. Really that's about it in a nutshell." Pressed about the uproar over Trump's immigration policies, he demurs. "At the end of the day, it's not really my fight, is it? Even though it's very concerning. I hear it, I'm very conscious of it, but what am I supposed to do, really?"

Asked about Australia's controversial detention of refugees, he shifts in his seat and smiles apologetically. "I really don't have much to say about that." In any case, his political opinions carry no influence, he says. "I don't really have a worldview. I'm just trying to make the best of what I've got at the moment, in having two families. That's just enough for me really."

The film, like the autobiographical book on which it is based, A Long Way Home, focuses on a true, inspiring story, he says. "It's about letting people open up their minds in so many different aspects. And so if we just keep it straight on that, that's great for me. I never intended to have politics in this."

It is PR protocol to laud your film's performers, but Brierley seems genuinely enchanted with his depiction on screen. "Sunny does an amazing job. The facial expressions that he projects are just phenomenal. No experience in acting at all and he's able to do that. I've seen the movie about 25 times now, and I can understand why it's so mesmerising when you're looking at this kid."

Patel, who won a Bafta and could win an Oscar for playing the adult Brierley, nailed the role, including the accent, Brierley says. Kidman – who adopted two children in real life – was ideal to play his adoptive mother. "They've talked so much about it that it almost feels like they're sisters."

Last week he was back in India – he visits regularly – and showed the film to his biological mother for the first time. "She was just in tears right from the start. It's so close to her, seeing the way it all really happened."

He considered bringing her and other Indian relatives to the Oscars, but decided the shock of the real la-la land – where he is attending a blitz of parties and receptions – would be too much. "They're very conservative people, and that's fine. They know of Bollywood, but not Hollywood. For someone as conservative as my mother to fly all the way from India to be among western culture …" He shook his head. "Her mentality is from 1946."

Brierley feels heavily invested in Lion. The title is drawn from his original name, Sheru, which means lion in Hindi. "The trajectory started in my mind. It became a documentary, then a book and now a film. I guess I've been pushing it in as many ways as possible."

The goal, he says, was to let other adoptees know they could trace their origins. "It was a book for other people like myself, in the hope that they would be empowered and educated to know that there is a light at the end of the tunnel."

Just as the train set Brierley on a new life, so, in a way, has the telling of the story. Before the book and the film, his job was helping his dad run a marine-gear retail business in Hobart, Tasmania. Now he is a motivational speaker, a gig that seems as if it could endure. "I told my dad I was taking a gap year, but it's a big gap year," he laughs.

It's not glamorous and he's not famous, he says. "I wouldn't fly my flag so high. I do get recognised, but not as much as someone like Dev Patel or Nicole Kidman."

The boy from Khandwa does share one trait with celebrities – an ambiguity about his age. Though it is not from vanity or the desire to prolong a film career. "I don't have a birth certificate." His best guess: 35.

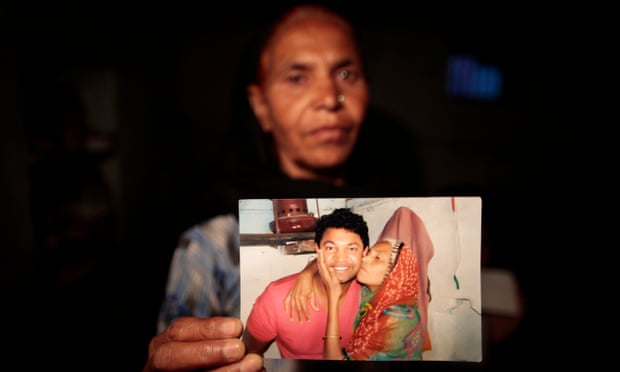

'My heart is bursting': an interview with Fatima Munshi, Saroo's mother

One day in 1987, when Fatima Munshi's son Sheru was five years old, he set off from their home neighborhood of Ganesh Talai, Khandwa, in the state of Madhya Pradesh to find his elder brother, Guddu, 14, who was scavenging for food at a railway station about 65km away. Evening came, and neither boy returned. A few days later, the police brought Guddu's body to her – he had fallen under a train. But they had not found Sheru, and so she set off to look for him herself.

"I went to Hyderabad, Bombay, Ajmer, Bhopal and Delhi to find him," she says, speaking on the telephone from her tiny, one-room house in Ganesh Talai, her voice loud and high-pitched, as it often is with people unaccustomed to speaking on the telephone. "I had lost my eldest son. I was determined to find Sheru."

Twenty-five years later, Sheru – now Saroo – arrived on her doorstep. It wasn't as much of a surprise as it might have been, she says, because he had always been in her thoughts. "I had so many dreams in which my son would turn up. He'd be this big man, a success in life, a film hero or something and he would come back into my life," she says.

The moment they met was intense and silent. Only two words were spoken: "Sheru" and "Maa" (Hindi for mother). "Since then, I have seen him about twice a year. When he is in India, he comes and spends the day with me. I cook for him and he leaves at night," she says.

Later, Saroo's adoptive mother, Sue Brierley, also travelled to India to visit Munshi. "The three of us hugged. That's all. It felt very good for us to be together," says Munshi.

The film, and her son's fame, have altered her life to some extent. She used to rent her room; Brierley has spent 300,000 rupees (£3,600) to buy it for her. Her bank account used to have the grand balance of 900 rupees (£10). Brierley paid £600 into it a year ago. But otherwise her life remains the same – living alone, washing dishes in a few local homes for around 1,600 rupees (£20) a month. "Working is mazboori [compulsory] for me. I have to work to eat," she says.

The tragedy of such a reunion is the language barrier. How can they express long-suppressed emotions and thoughts when Brierley has no Hindi and Munshi no English? "There is so much I want to say to him. My heart is bursting, but how do I do it? We just look at each other. He has another life and I accept that, I am happy for him," she says.

The next day, when I call her again, Munshi refuses to speak. She tells a local reporter who is at her house that someone from the film team called a woman in the village to tell Munshi that she should refuse to speak to the media. She sounds angry. Before she shoos the reporter out, she says: "I will only speak when my son is here. My son is more important to me than money. The media are making a mockery of my life." Interview by Amrit Dhillon

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/feb/24/saroo-brierley-lion-oscars-interview

0 Response to "Movie About Boy India Likes to Draw"

Post a Comment